"Passion, Process, and Goose Bumps on a Corpse"

PEOPLE DON’T USUALLY ASK where I went to school, or how long I’ve been doing what I do. They ask something simpler, yet awkward for me: “Where do you get your passion for this stuff?“

Instead of a “Gee, I don’t know” or “Genes, I guess,” this time I’ll answer directly, but first let’s get a little disclosure out of the way: It involves a red bird dancing with a green bull-frog.

IT WAS THE ‘60s and Uncle Richard and Aunt Marsha were living in Munich, where he taught high school math and science to US servicemen’s kids while she organized war protests and worked, maybe a little too diligently, to imbue her natural troubadour voice with an authentic whiskey-and-cigarettes texture. When summer rolled around she, Uncle Richard and my 3 little cousins would make what she called “the schlep” back home to visit us “relates” in Fresno and Los Angeles.

When dusk came, my sisters and I, a dozen cousins, and a knot of neighbor kids would scramble for the six faded canvas butterfly chairs in the backyard and hastily drag them into a ragged semi-circle. The smaller ones would tussle and tumble in, two to a chair. Eventually parents and sundry aunts and uncles would wander out and bark orders for kids to give up their seats. But this was a long-anticipated Special Occasion, exactly the kind of formative experience that proved to stiffen a young person’s spine: After a united show of juvenile defiance, the old geezers would shuffle off to lean against the apricot tree or unceremoniously fold themselves onto the grass next to the kids who hadn’t shown sufficient hustle to score a chair.

Aunt Marsha – we all called her Moofie – would set herself up in a folding chair in the center, pull her Martin out of its battered case, and chat about traditional songs and what they meant. (I recall being surprised that a “mule skinner” didn’t actually skin mules, and that her guitar teacher in Boston, not Peter, Paul & Mary, had written “Puff the Magic Dragon.”) When she’d finished tuning, we’d all get quiet, close our eyes and listen to this masterful musician/storyteller strum, pick and sing the first little song, framed only by a simple but intoxicating stew of summer-evening sounds: crickets chirping, feet tapping, and young hearts pounding:

Way up yonder above the sky

A bluebird lived in a jaybird’s eye

Buckeye Jim, you can’t go

Go weave and spin, you can’t go

Buckeye Jim

Way up yonder above the moon

A blue jay nest in a silver spoon

Buckeye Jim, you can’t go

Go weave and spin, you can’t go

Buckeye Jim

By now, jaws large and small were going slack, time was slowing down, and the first stars were coming out, but Moofie, well, she was just getting warmed up:

Way down yonder in a wooden trough

An old woman died of the whoopin’ cough

Buckeye Jim, you can’t go

Go weave and spin, you can’t go

Buckeye Jim

Way up yonder in a hollow log

A red bird danced with a green bull-frog

Buckeye Jim, you can’t go

Go weave and spin,

you can’t go Buckeye Jim.

* * *

IMAGINE IT: a “magic kingdom” in a hollow log. It could’ve been the first, fifth or twenty-fifth time you’d heard her sing that almost nonsensical song, but every time it was fresher, more magical and more memorable than your first trip to Disneyland.

* * *

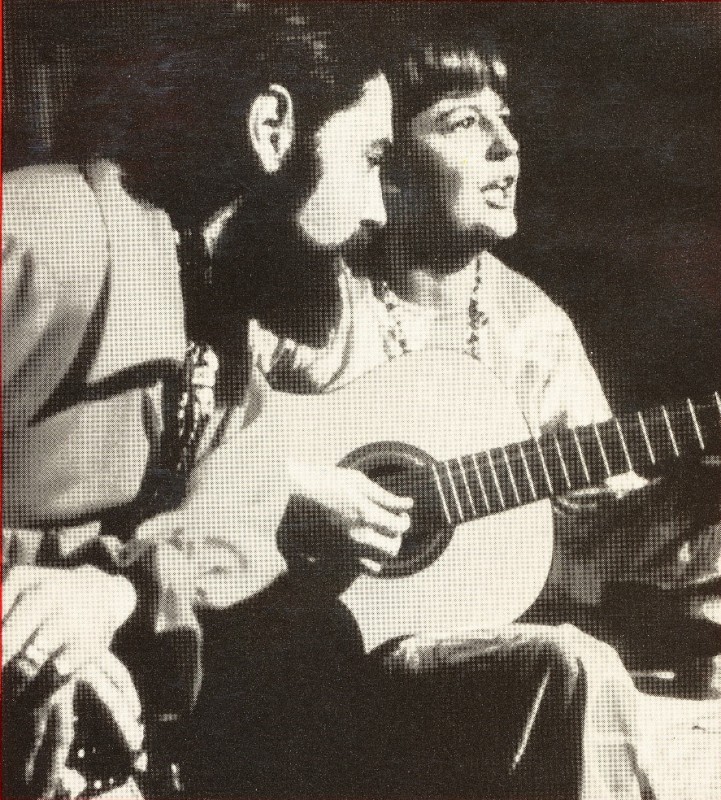

MOOFIE AND HER SINGING PARTNER, Jim Orr, went on to record American folk songs under the name their record label gave them, Beulah & Leroy. In retrospect, an attentive music critic might say Moofie (no one ever called her Beulah) was in the Joan Baez/Judy Collins tradition, but with an effortless ability to channel the ache of Emmylou Harris, the howl of Janis Joplin, and the haunt of Grace Slick at their peak. Those who knew her would likely acknowledge the description, while adding that all of that was just an expression of something deeper: an irreverent, earthy authenticity that lit up every room she ever inhabited.

Moofie cast spells, pure and simple, and those memories have fueled a life-long quest to give others what she gave me: involuntary muscle contractions at the base of the epidermis, an unconditioned response of the Sympathetic Nervous System known as the Pilomotor Reflex. Goose bumps.

* * *

AS THE YEARS WENT BY there were other artists whose live concerts would raise goose bumps on me. Genesis at the Roxy on Sunset strip in ’73. Mahler symphonies at Carnegie and Disney halls. Leonard Cohen at the Paramount. The Decemberists at the Britt Festival. Chris Webster singing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow/What a Wonderful World” at my friend Fish Doc’s house concerts. It seems every time the reflex distorted the surface of my epidermis I redoubled my efforts to puzzle out how to duplicate the effect in others. There just had to be a formula for it.

* * *

WHEN NOT IN CLASS, I spent my college years working in audio and record stores, writing concert and album reviews, interviewing pop and rock artists of the day and ploughing through engineering textbooks to try to figure out how to produce a reflex in the home listening room that bore some semblance to the one that seemed to “just happen” whenever Moofie reached for her guitar and started singing, say, “Me and Bobby McGee.” Thing was, by the time she got to the verse …

Well I’d trade all my tomorrows for one single yesterday,

Holdin’ Bobby’s body close to mine.

Freedom’s just another word for nothin’ left to lose

Nothin’, that’s all that Bobby left me,

But, feelin’ good was easy, Lord, when he sang the blues

Feelin’ good was good enough for me,

Good enough for me and my Bobby McGee

… you’d be dabbing at your eyes and struggling even to nod when the person next to you whispered, half-hoarse, “This would put goose bumps on a corpse.” I’d think of that whenever I felt I was making progress on the formula. I had a long way to go before getting an audio system to duplicate that particular “outcome” in a stranger’s living room.

* * *

IDEALLY, YOU SETTLE INTO your screening room and press “Play.” The lights dim. The room gets still, an inky black silence. You take a deep breath; the air is fresh, clean, stimulating. The picture comes up; it’s huge, vivid, pulls you into another world. The sound swells up; even at low volumes, it’s riveting, reach-out-and-touch-it stuff. A bus or streetcar goes by in the distance – only a passing detail, but your feet pick up the rumble; if it were any closer you’d swear you feel the brush of wind on your face.

On your end, getting goose bumps is a natural part of great movie and music experiences in the home; they “just happen.” On ours it’s not so simple: It’s an engineering driven process, 30 years in the making. I’ll save the outline for another blog.

Toward the end of that process we hit a point where the science has taken us as far as it can – time to put away our acoustic equivalents of X-ray and CAT scan machines and just sit down in the quiet. I dim the lights and spin up my reference music tracks and movie scenes, tools I’ve been using for years. I listen and call out a few tweaks to the filter settings – a decibel or two here, a few tenths there, admittedly such small adjustments that my engineers have to lean in and squint to see the change in the frequency response curve.

But the truth is, when the system sings, the room glows in the right ways, and we’re getting so close to magic you can almost taste it, I’m not looking for a curve. I’m running on instinct, looking for the Reflex. If I’m looking anywhere, it’s backwards, to the beginning.

* * *

YOU COULD SAY OUR PROJECTS, scattered around the world, are a long way from my Aunt Moofie leaning forward on a folding chair in a Fresno backyard, singing about a red bird dancing with a green bull-frog. But I’m struck by how close they really are. The magic of a story so fresh and well told that you’re transported to some other place. Maybe an 18th century opera house. Maybe a creaky pirate ship, or a 23rd century space ship. Or, if you’ll allow me, just “way up yonder in a hollow log.”