"The Time a Stiff Caught Fire"

In early ’74 my roommate and I launched a small-town petition drive to rescue an obscure young pop artist whose first major-label record had debuted and, a few months later, quietly died, or “stiffed.”

The album’s unusual — and previously unexplained — rise from the grave and ascent to the top of the national charts was the subject of a short memoir I wrote for the August 1987 issue of Sacramento NPR station’s member’s magazine. The album’s producer, Michael Stewart, read my piece and called to corroborate some particulars and thank me for finally solving the mystery.

Before signing off, Michael asked if he should get word to the artist. I thought about it and said, well, maybe after I’ve written the full version of the story. Michael asked when that might be. “When he’s ready to retire,” I said.

With retirement around the corner, here it is, as promised over 30 years ago, the true story of how Billy Joel caught fire with Piano Man.

I WAS A SHY, NERDY KID WRITING ROCK REVIEWS for the college paper.

This was in the early ‘70s, when the stuff of the LP – oil – cost next to nothing, which only encouraged record companies to sign all manner of sketchy talent in the hopes that somehow one of them would catch on with the student crowd.

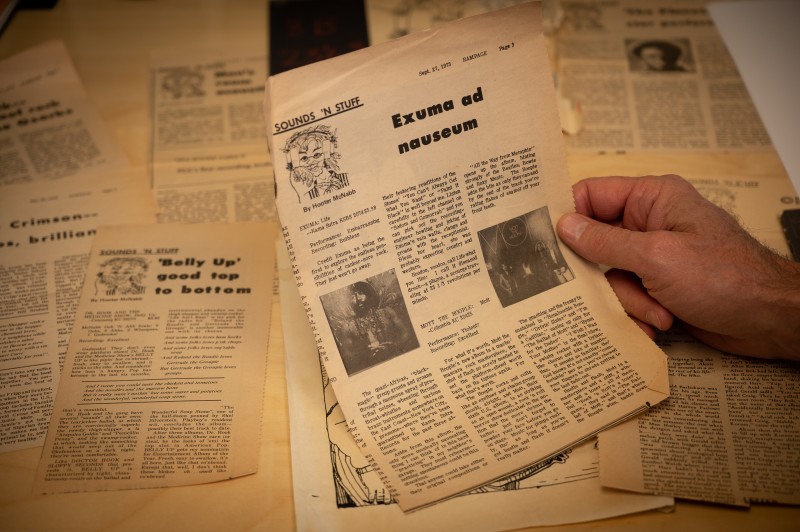

The delivery man was dropping off 20 to 30 promo albums a week because these same companies were dishing out free albums to any scribbler who tacked “Music Critic” onto his letterhead – even a small-town, wannabe Rolling Stone writer like me, hiding behind a hokey moniker, Hooter McNabb, in a smudgy weekly called the Fresno City College Rampage.

When not in class or writing reviews, I worked the counter at Sun Records, on the back side of the Sun Stereo store on Blackstone Avenue. It was to be a minimum-wage stepping-stone on my way to a hoped-for promotion to the hi-fi department, where the older sales guys drove Porsches to work and got to demonstrate the latest Swiss-made turntables, McIntosh amps, and big JBL and ESS speakers.

Meanwhile, back in the Record department, customers were starting to ask what I thought of Hooter McNabb’s latest pronouncements, excerpts of which were being read on-air by the main FM rock station in town.

“Hooter McNabb?” I’d say, running my fingers through my shaggy mop. “Does that sound like a guy’s real name to you? What kind of music critic hides behind a pen name?”

It had its tingly moments, this secret, scrappy new Hooter McNabb side of me.

* * *

THANKS TO THE FREE VINYL rolling in and my liberal discount privileges at Sun, I’d exhausted my shelving unit’s 2,000-LP capacity a few months earlier, had been leaning new acquisitions 80 to 100 deep against the bedroom walls, and stacking the rest in 2-foot high piles around my waterbed, until one day I had to admit that my treasures had become tripping hazards.

* * *

I CALCULATED that scooting my waterbed just three feet toward the center of the room would free up enough space to expand my shelving unit down the wall’s full length, increasing total capacity to 10,000 albums.

I saved up and one day in January ’74 I returned from the lumber yard, piled the bricks and boards on the linoleum floor in the living room, and fed the garden hose through the bedroom window so I could drain the mattress enough to horse the heavy, sloshing thing out of the path of progress.

I got the siphon going, then turned to the last remaining obstacle: a ragged, chest-high pile of promo albums I’d dismissed as beneath reviewing, selling or even giving away. Stacked and abandoned at the far end of what would be my glorious wall, these dusty cast-offs had nothing left to look forward to but nocturnal relocation to the dumpster behind Pepe’s Tacos three blocks east.

I lugged the first armful of the doomed from the top of the pile to the hallway, maybe 15 feet away, that ran between my room and my roommate’s, now a temporary staging area for the midnight run to Pepe’s.

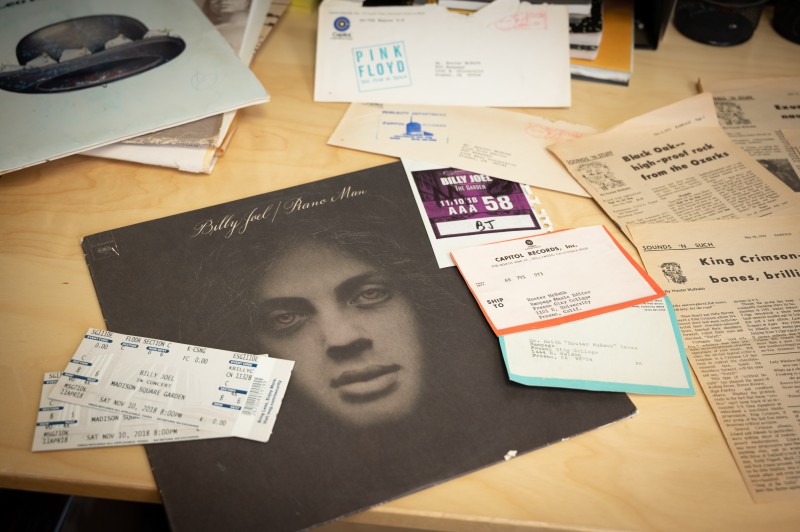

When I returned from my second hallway haul, I noticed the album now on top featured a close-up of a guy whose eyes seemed to bulge out a little, like a frog that had swum up from the bottom to have a look around and had caught a troubling glimpse of impending doom.

When I bent over to hoist the third and final load, those eyes, maybe 6 inches away, seemed to lock on mine, unsettled me, like I’d violated the guy’s personal space or something. I recoiled a bit, grew defensive, reflexively thought, “What kind of aspiring artist stakes his career on a froggy cover shot?”

A few more seconds into our staring contest, I noticed the record label logo in the upper-left corner, and thought, “You get yourself signed to Columbia Records – home of Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Janis Joplin, Miles Davis – and this is what you come up with? Are you clueless?”

I decided to spin it up, settle the question while I continued working.

* * *

HALF-WAY INTO SIDE ONE I went back to the turntable, gave the album a wipe with my record brush, zapped it with my anti-static gun, brushed the stylus clean and spun it up again from the beginning. I turned up the volume and took a seat on the splintered wood frame that corralled my flaccid mattress.

One of the tracks could’ve pumped up the crowd on Joe Cocker’s raucous Mad Dogs and Englishmen live album. Another could’ve slotted right in on a chiming Gordon Lightfoot album. Yet another seemed lifted from some lively new Broadway production. The genres were varied, but the song-craft surprisingly consistent.

It was nothing like my usual weekend fare – Genesis, King Crimson, Jefferson Airplane – but the tunes were catchy and the mix of influences fresh. There was some Tin Pan Alley, Elton John Tumbleweed Connection, Mr. Bojangles, and ringing anthem-like choruses that seemed drawn from the same well that fed a promising new guy, Springsteen.

There was evidence of a Randy Newman-like gift for melody and something akin to Tom Waits’ knack for lighting small, slice-of-life vignettes with an almost cinematic glow.

The whole vital and occasionally haunting thing was shot through with a confessional, regular-guy vibe that, though tinged with corniness now and then, was the perfect antidote to the sometimes-operatic bombast of my prog-rock indulgences of the day. This bulgy-eyed bloke didn’t take himself all that seriously, made it sound easy, like the songs had just popped into his noggin and out his fingertips while he effortlessly sang along.

He sounded young, like he hadn’t found his true voice quite yet, and almost annoyingly talented.

In the meantime, he had me, a greenhorn posing as a heard-it-all music critic, singing along on the first play.

I stared back at those eyes. Who is this Billy Joel, and how had he wound up with the wretched and doomed at the bottom of my Tower of Scorned Flotsam?

* * *

MY ROOMMATE RETURNED, surveyed the lumber piled in the living room, the vinyl detritus clogging the path to his room, and the grimy garden hose in mine, and shot me an odd look.

“Take a seat, man,” I instructed. “You gotta hear this.”

He shrugged and hunkered on the bed frame while I dropped the needle on the last track, side 2, nursed the volume up.

“OK, here we go, Marty,” I barked over the music. “Listen how he’s playin’ with us, settin’ us up, something’s coming, hear it? OK, hold on, here comes the hook, OK, Marty, listen right … right … there! My God, isn’t that brilliant?”

Given the din and squalor, your standard, paid-up roommate might be forgiven for rising up and twisting the tonearm off your turntable.

But Marty Sherwood, who worked the counter with me at Sun Records, was mellower, and a better listener, than anyone I knew. And Marty kept his eyes closed, shut it all out, and just listened.

After we’d played through both sides, and with my waterbed still draining onto the lawn, Marty and I resolved to do whatever it took to help launch this guy.

It wouldn’t be the first time. A few years earlier, Marty dug up an obscure track by an obscure duo during his stint as Music Director at Fresno’s Top 40 radio station. He slipped it into rotation, watched it take off and spread across the country, ended up a Top 10 hit nationally. He had the framed Gold Record on his bedroom wall as a reminder that a good ear and a little effort can make a difference.

And I was Hooter McNabb, making a stop at the Rampage on my way to Rolling Stone.

So, really, with credentials like those, and material this strong to work with, how hard could it be?

* * *

ON MONDAY MORNING I phoned Columbia Records’ promotion man in San Francisco, Ken Reuther, thanked him for sending the album, announced that Billy might be the most natural talent I’d heard in my entire reviewing career – all eleven months’ worth – but that somehow I must’ve misplaced the press kit. I wondered if he could slip another bio and a couple of photos in the mail right away for my upcoming feature in the Rampage.

Reuther said he didn’t have anything to send. I didn’t understand.

He backed up, said he’d worked the artist’s first record, on a tiny label, a year or two earlier, and most of the few people who bought it were probably just friends and relatives. Said Columbia’s A&R [artists & repertoire] guys in New York heard some potential, signed him, but the new album had gone nowhere in the months since its release.

“Well, you must have a photo of the album cover I can run with the feature. I need something.”

He countered that Columbia was busy pushing out a new pop or rock release every day or two, and that I “should’ve written it up when it was fresh, maybe it would’ve made a difference.” Once in a while a new artist takes off. The others disappear. “Just the way it works,” he said.

“But this guy’s got talent, songs, and he can sing,” I protested. “A couple cuts have big hooks, like radio hooks, man. He deserves a second shot.”

Reuther seemed to consider Billy’s Columbia debut as that second and final shot.

“C’mon, Ken, you gotta promote him a little, he’ll take off,” I pleaded.

It was too late: The guys in the New York office had called in Billy and his producer, Mike Stewart, sat them down, said everyone gave it a good try, but it hadn’t worked out: They wouldn’t be exercising their options for any follow-up albums. It’s over.

It felt like someone was wringing my intestines like they were sopping wet bath towels.

Reuther must have sensed I was shaken. “Hooter,” he said, as if to console me, “you work in a record store, right? When was the last time you saw a stiff catch fire?”

* * *

‘STIFF’ WAS FREIGHTED WITH THE SAME FINALITY and fetid stench that “liquidation bankruptcy” carries in banking. Dead and stinking.

Stiffs were melted down to make more vinyl for some other random hoser’s albums. Or, worse, they got a hole punched in their covers and were relegated to those wobbly 99-cent clearance bins in the dim corners of record stores across the land. At Sun, every Saturday morning we’d move our four decrepit cut-out bins to the parking lot, just outside the main entry. Within an hour a certain species of circlers – gaunt guys with sunken eyes and soiled trousers – would catch the scent and silently descend with talons out.

The term stiff had been gaining currency for a while, as the pop record business steadily evolved away from its artist-driven roots, toward something impersonal, even clinical, driven by the need to maximize the label’s bottom line.

By ’74 the reign of the visionaries and “golden guts” – the talent scouts and A&R [artists & repertoire] guys with a gift for finding needle-in-a-haystack type artists and guiding and nurturing them – was in decline. Holdovers like Clive Davis and David Geffen stood out in the new order because their golden guts glittered against the dark backdrop of what the corporate, consensus-driven machine was fast becoming.

A similar darkness had come over the radio business a few years earlier. By the time Columbia sacked Davis in mid-’73, the ranks of radio station Music Directors were already thin and growing thinner by the month.

In both industries, creative vision and gut instincts were being replaced by centralized corporate planning and automation. The relationships between corporations and artists had become transactional: “No traction, no future.”

ONE OF THE NEW RULES was that a new album by an established artist had maybe 8-10 weeks to get traction – buzz, reviews, air-play, sales – before being written off as stiffs. The runway for new artists was half as much. The math in Billy’s case was brutal: Piano Man had been in stores for 15 weeks.

I had a dark vision of the last copy of Piano Man, maimed by a perforated corner, being picked over by the carrion eaters, until no trace remained of Billy’s genius anywhere.

I tried to envision a world in which Piano Man defied the odds and “caught fire,” in Reuther’s words, and became the start of something magical.

What came to mind instead was the reality that it was simply too late. All of us had failed Billy and his God-given talent, from Columbia executives to radio station music directors, and on down to the little players in the hinterlands, like me, whose role was simply to spot, describe and highlight such talent, and resist the impulse to chuck their work, un-played, into foul dumpsters in the dead of night.

I was getting the disturbing sense I’d become a small cog in a dark machine I only partially understood.

Stewing on stiff, and visited by visions of dumpsters, ovens and cut-out bins, forced me to confront the churning in my gut, and its spread: I was starting to get a sharp, acid-like taste in the back of my throat.

I didn’t know what form it would take, but somehow I had to do something.

* * *

I REMEMBERED MY MANTRA from a few transcendental meditation sessions I’d had six months earlier, figured maybe it was time to resume closing my eyes and silently intoning it, see if it would settle me down, make the churning go away. When I slowly opened them twenty minutes later it seemed the problem might not be as complicated as I’d imagined. Maybe the solution was as simple as calling over to K-FIG, the local FM station where Ray Appleton presided over the local rock scene. Somehow, I hadn’t previously thought of it.

Appleton was known to hang out with Bowie and other rock royalty I only scribbled about from a distance. It was Appleton who’d been quoting my reviews on the air, and the Rampage had run my feature spread on him six months earlier. I’d simply ask him to consider working a track or two into his playlist. There was a chance he’d figure he owes me one without my mentioning it.

It was calming to contemplate that a guy like Appleton, an icon in town with an almost encyclopedic knowledge of rock music, would consider doing me and my froggy-eyed foundling a favor.

He took my call, sounded relaxed and happy to hear from me.

“Sounds like great stuff,” he said, sympathetically. “But didn’t it stiff? It stiffed, right?”

I couldn’t manage a response. As the seconds drug on I started hoping the silence would ask the favor I couldn’t. But we both knew it wasn’t going to happen. “Bring me something fresh,” he offered, “and I’ll try to help.”

This was going to take more than a quick call to a sympathetic colleague. It was going to take playing the only card we had left.

So I went to Marty, said it was time for him to call in a favor from his days at KYNO, that Top 40 station I mentioned.

* * *

ANYONE WHO KNEW POP RADIO in those days would say, “You’ve got an inside track at KYNO? Well, yeah, man, that ought to do the trick.” To understand why they’d say such a thing, there are a few things you ought to know about Fresno’s role in the remaking of the American radio business.

Set in the middle of central California’s vast San Joaquin Valley, Fresno is surrounded by the most fertile agricultural land in the world, but little else. If you want to escape the flat valley floor for, say, San Francisco to the north or Los Angeles to the south, you faced a drab 3-hour drive down Highway 99 either way, enlivened only by volleys of large, colorful insects splatting on your windshield, and the intermittent need to veer around a tumbleweed blowing across the highway.

In the ’60s and ’70s we young Fresnans assuaged our hipness deficit by reminding each other, “Well, yeah, but if a song takes off here, look out, it’s gonna be a hit everywhere.”

Like most kids, I grew up thinking there was something besides bugs in the thick Valley air, something invisible that somehow put us in the pop vanguard. It turned out that invisible something had a name: KYNO.

It was in the ’60s, in Fresno of all places, that Top 40 programming – the formula of what songs, in what order, separated by what kinds of transitions, DJ chatter, commercials, news breaks, announcements, station jingles, and so on – was broken down, rearranged, retested, tuned, and ultimately turned into a machine that changed radio from coast to coast.

Bill Drake and his business partner, KYNO owner Gene Chenault, came up with “music sweeps” timed to get underway when competing stations went to the news break at the top of the hour, so when you punched through your station presets they’d snare and hold you, unmolested by new or commercial interruptions, for up to 40 minutes at a stretch.

Drake and Chenault drilled “boss jocks” on how to be smooth and brief (“less talk, more rock”). They set up listening panels to decide which songs made the cut, and slashed the time allotted for commercials to under 14 minutes an hour. They finessed the 2-second transitions between songs like Leonard Bernstein blending the brass with the string sections of the New York Phil. The result was a palpable sense of velocity and forward momentum: Every detail was designed to pull you through your day.

What had the whiff of a chemistry lab experiment came to be acknowledged as the beginning of disciplined market research in American radio broadcasting. By the early ’70s the list of stations who’d turned over their programming to Drake-Chenault Enterprises had gone from one – KYNO – to 350, from powerhouse KHJ in LA to WOR-FM in New York.

It was said that if you owned the most lucrative Top 40 station in your market, and one of your struggling competitors had just inked a programming deal with Drake-Chenault, you were probably 120 days away from requiring the services of a bankruptcy attorney.

The juggernaut was chronicled in Time magazine and major newspapers across the land.

KYNO and Bill Drake’s success in the sixties foretold what the radio and the record industries would look like a decade later: corporatized, centralized, automated.

* * *

BILL DRAKE SO PROFOUNDLY RESHAPED American radio programming that, a decade after he’d ditched Fresno for a mansion in Bel Air, even non-Drake stations were still monitoring what was getting air-time back at KYNO, the old test lab where Drake had perfected the formula and loosened the reins on station management just enough so they could “break” a new song on their own now and then.

That was why, when record company sales reps dropped into Sun, they’d often mention that the Bay Area and LA pop radio stations “keyed” their programming on what was happening in Fresno. The big-market stations had too much to lose by making the wrong song choices.

With all that history, and tucked away in the “demographically average” Valley, KYNO was the ultimate test lab. Just follow their lead.

* * *

IF WE COULD GET MARTY in front of his old KYNO comrades, persuade just one of them to slip Billy into rotation, get a toehold, there were paths, maybe more like highways, for it to fan out to dozens, maybe hundreds of those other homogenized Drake-programmed stations across the land.

When I squinted just right, I could sorta make out that the combination of Marty’s Rolodex, together with the coincidence of being a few blocks from ground zero of the Drake Revolution, could be all we needed to blast Billy into orbit. Just get it on KYNO, and the Drake network will do the rest without our even having to ask. Might’ve been the first time I considered myself lucky to be from the buggy San Joaquin.

* * *

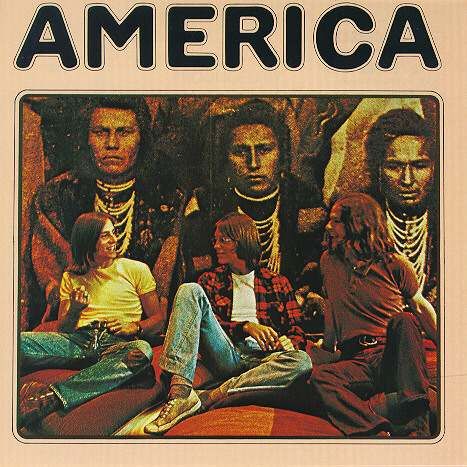

MARTY HAD HIS OWN REASONS to look forward to a reunion. As KYNO’s Music Director two years earlier, he’d pushed to get into rotation a track off the debut album of a couple of Americans living in a tent in England, convinced that these dopey, scraggly guys with their Neil Young Harvest vibe could be huge. The album had first been released in the UK, where it hadn’t gotten traction. The record label thought they’d give it a try in the US before throwing in the towel.

Marty’s boss had the leeway to put the US release into rotation but didn’t share his enthusiasm.

Marty stuck with his gut, went back to the boss until he finally threw up his hands, said, OK, fine, he’d refer it to Drake’s lieutenant in LA, who came back with a resolute “No.” After that, each of Marty’s subsequent entreaties must have come off like, well, a broken record.

Later, another station in another market took the risk. Turned out that they,  not Marty, KYNO and Bill Drake, were the ones to break America’s first single, “A Horse with No Name,” went to Number 1 and stayed there for weeks. By then Marty had been let go, a victim of “automation,” they’d said.

not Marty, KYNO and Bill Drake, were the ones to break America’s first single, “A Horse with No Name,” went to Number 1 and stayed there for weeks. By then Marty had been let go, a victim of “automation,” they’d said.

In hindsight, Marty’s hope of persuading KYNO to roll the dice with Billy might’ve been about more than just reconnecting with the old gang.

Might’ve been about feeling relevant again.

* * *

WHEN REUNION DAY CAME it was bear hugs all around. Marty beamed, suggested Billy and Piano Man could be huge. “KYNO has a special place in radio history. This guy could be part of that story,” he said. “Let’s do this together.”

The senior KYNO guy went first: “Marty, we miss you and would do most anything to help, man, but you know the first rule of Top 40 radio because you drilled it into us here: Never program a stiff. It sounds like an adventure, but it’s so basic we’d lose our jobs over it.”

No one else said a word, nor needed to. It hadn’t been just 3, 4 or even 5 weeks since Billy’s big-label debut; it’d been 12. Picking hits off a fresh release from some new artist was one thing; breaking out shovels to disinter a no-name stiff was unthinkable.

Marty shuffled off to pitch a few other program managers and music directors around town, with the same result: A stiff’s a stiff, nothing to talk about, but, hey, great to see you again.

* * *

IT WAS TIME TO REGROUP, lower our gaze from galactic to grassroots. I toted my promo copy to Sun, asked my manager, Mike Chakerian, if I could give it a spin on the house system, try to kick up some interest among the walk-ins, people who didn’t know that albums by new artists had unofficial sell-by dates, like cartons of milk.

Chakerian went along, even offered to order some so we’d have them to sell, maybe set up a display and signage wherever I wanted. Said we could start with a couple of boxes, see how it goes.

He took the album, disappeared into his office to place the order, re-emerged a few minutes later, handed it back.

Piano Man had come and gone, he reported, no LPs available and no plans for it to go back into production.

Sun Records was the biggest record store in the 400 miles between San Francisco and LA, and we couldn’t get our hands on a single album, let alone a couple of 25-count cartons of them.

I hadn’t seen it in the usual cut-out bin graveyards around town, which left me with a sinking feeling that the vultures might have already had their way with Billy and, if there were any last, unsold copies of his big-label debut in the wild they could be sliding around in the back of a pickup on its way to an oven somewhere.

I paced around the bins until the reality sank in that Chakerian’s OK to play my promo copy was the only play I had left.

I plopped it on the turntable and dropped the jacket in the “Now Playing” holder. Somehow it got stuck at a funky angle. While jiggling it to square it up, it dawned on me that it might draw more attention if I left it crooked.

* * *

I LIKED THE EFFECT, thought I’d take another lap around the bins for more inspiration. This time I noticed that the rough-sawn barn-wood walls gave the place a muted, dingy feel just aching for some vibrant, inspirational wall art to make the spirit soar.

I fished around in the supplies closet, came up with some Marks-a-Lot pens and poster-size sheets of bright yellow construction paper to fill the void.

I wrote SCREW THE ESTABLISHMENT, GET BEHIND THE NEW TALENT! in six-inch high letters inspired by a Jefferson Airplane concert poster, and thumb-tacked my hortatory masterpiece to the wall, making sure it was maybe 10 degrees off-kilter, like the album jacket. Within 15 minutes I’d tacked up two more.

I went back to the closet, scrounged a legal-size notepad, scrawled PETITION! across the top in big, block letters, made columns for names and phone numbers, and set it down in the middle of the counter where customers lined up to pay.

It was time to work up some kind of presentation. Seemed I was still on a roll so I went with the first thing that popped into my head: When customers came to the counter to make their purchases, I’d motion to the kitty-wampus album cover next to the turntable, then point to the posters, then the speakers.

Then I’d say in a world-weary way, “Hear that? Music that solid and the record company won’t press any more albums, told him it’s over.”

I’d let the insult hang in the air for a moment, then shake my head disapprovingly and finish it off with, “There’s the petition, man.”

It was surprisingly easy work. As customers came in and the pages filled up I started entertaining the strange notion that I might be a PR wiz-kid-in-the-making or something.

But in those days, with Watergate in the news, and a growing stick-it-to-the-Man vibe in the air, all a guy had to do to extract a protest signature and phone number was set a pen next to a petition, then turn around and fumble with the cassette tapes or rolling papers display while they waited to pay.

* * *

WE SNAGGED A COUPLE HUNDRED NAMES in barely two weeks. I felt like a regular Che Guevara, called Reuther, my heart pounding.

“I’ve been playing my promo copy in the store and people are getting riled up down here, man, a petition sprang up with a couple hundred signatures already. It’s like an underground movement kicked up out of nowhere. We need albums to sell and I really need that bio and photo so I can write the review, gonna be my biggest feature ever. Appleton’s probably gonna read it on the air!” I boasted.

They were outsize claims for a 135-pound freshman with a minimum-wage job and a borrowed soapbox from a community college journalism department.

Reuther ignored the news of the dangerous insurrection brewing down in the sleepy Valley, repeated that he didn’t have any PR kits to send, then divulged that, like everyone in the company, he had to “work what’s on the priority list” handed down from the corporate office on Monday mornings. He added that Piano Man had dropped off that list quite a while back.

It was clear from the way he said Priority List that he could get himself fired for spending time on something that had been stricken from it. While that was sinking in, Reuther shifted gears, grew expansive, reminisced about growing up in New Orleans, said that Fats Domino was a regular in his dad’s floral shop. After 15 minutes I still hadn’t converted him to our side in the Epic Struggle, but I was warming up to him.

Probably helped that he hadn’t dropped another S-bomb on me.

* * *

REUTHER CALLED out of the blue a couple days later, said he’d gotten some branch managers to poke around and one of them had turned up a single left-over carton of 25 albums at Columbia’s Western US pressing plant down in Santa Maria, near Santa Barbara. He could get it shipped to the store. I registered a little whiff of co-conspiracy in his voice. Gave me a little hope.

Then he returned to a more business-like tone: “That’s it, there aren’t any more anywhere. And you understand that we can’t do another pressing run just for you guys in Fresno, right? We’re clear, right?”

When the carton showed up I grabbed my Marks-a-Lot, wrote “Billy Joel” on a white plastic record divider and crammed it and 20 albums in the bin. I stuffed the remaining five behind the counter as “reserve stash,” as if it was a precious cache of exotic weed or something.

Marty and I started calling petitioners, announced we’d scored the last of Billy’s pop masterpiece, strictly first-come, first-served, so hurry in before they’re gone forever. People were mellow, even gracious about it, said they’d drop by next time they’re cruising down Blackstone, but precious few rolled up with the $3.99.

After a couple of days I started bugging random customers who’d come in for Dark Side of the Moon or Goodbye Yellow Brick Road or whatever to spring for Piano Man as well.

It was slow going in the beginning and only got slower over time. Customers seemed to be getting used to the posters and petition, seemed to be tuning them out. Even the usually chatty stereo sales guys stopped dropping in and asking how our revolution was going. By the time we sold the last copy of Piano Man in the bin, we were spent.

* * *

IT WAS TIME TO FACE FACTS. Our pals in local radio wouldn’t touch it. The petition drive had stalled out. Columbia’s cupboard was bare, and now so was Sun’s.

I slipped my promo album back in its jacket. Dumped the posters, stowed the petition behind the counter, next to the reserve stash. Resumed playing established artists on the house stereo. Moved on to something else, something not so wrapped up with rage and righting wrongs. Something forgettable.

A week or two went by, then on a Saturday morning the store manager rang me back in the Record department, said one of the sales guys was stranded at home: the Porsche was waiting on parts and the Norton Commando wouldn’t start. He needed me to cover for him as it was the store’s big annual one-day “Midnight Madness” sale event. People were already streaming in.

It was the break I’d been waiting for since the day Sun hired me six months earlier – my first chance to work in the audio department. If I survived the test, my days of working a cash register in the back for $1.65 an hour could be over. I’d be making a lot more money, get half-price deals on stereo gear, and still be entitled to my discount on albums.

I skipped down the connecting hall into the main sales floor, where I immediately picked up an intriguingly resonant voice off to my left, made a little jog in that direction to see if I could put a face to it before reporting for duty at the sales counter.

As I approached, the salesman helping the guy gave me a get-me-outta here! look and peeled off to wait on other customers while I was still heading in his direction.

The voice belonged to a Dave Butler, who introduced himself as an engineer in town who’d dropped by to have another listen to the ESS floor-standing speakers and the amplifier and turntable packaged with them.

It was a righteous rock rig in the day but by Dave’s grim account, every time he popped in, the sticker was still stuck at around $1,400 and his salary hadn’t changed for the better, either. They weren’t part of the sale and he couldn’t swing it at the full retail price shown, but wanted to know how the strange, accordion-like tweeters worked so he’d be informed “when the time comes.”

It was a pleasant enough chat, two audio propeller-heads indulging in a Saturday exploration of a shared passion, though there was a gauzy, “one-of-these-days” dreaminess about it.

At some point the conversation began to peter out and I thought maybe I should wait on someone who’d come in intending to take advantage of the sale. I excused myself, was half-way to the sales counter when it occurred to me that, based on his questions, Dave had probably never gotten a demo of what the system could do when exercised a little, let alone in pedal-to-the-metal mode.

I made a detour to the main sound-room, came back with Joe Walsh’s solo album, the one with “Rocky Mountain Way.” I spun it up, cranked the volume, made the whole store pulse to Walsh’s power-chording guitar going tot-tot-tot ta-DAH and whiney-nasal singing:

Crying ’cause the story’s sad

Is better than the way we had.

Within seconds, Dave and I were both hunched forward, staring fixedly at those big, squat, thumping speakers while sporadically making short kicking motions with our feet, and dipping a shoulder now and then – displaying what a big-city culture snob might characterize not as dancing per se, but as a couple of long-haired Valley yokels suffering mild, upright seizures of some kind.

When the spectacle had run its course, we launched into a spirited discussion of the 12-inch woofers. Dave’s voice was booming.

That’s when it hit me: This guy standing in front of me, my new buddy, wasn’t just some generic engineer, he was a broadcast engineer, and an occasional on-air announcer.

That’s where I’d heard that voice: Sunday afternoons on KFYE, Fresno’s “soft rock Y94 FM.” And our random encounter afforded me one last chance to get Billy over the hump, a Hail Mary that I knew could end my hi-fi career in the first hour of its first day.

* * *

I MOTIONED TO THE FRONT DOOR. Dave followed me out to the parking lot, where I paced back and forth, my heart thumping while the rest of me was trying to summon the confidence of my inner McNabb. I abruptly turned around and declared I was going back in there to sell him the system of his dreams at the store’s direct cost. Said I’d show him the dealer cost sheets, would probably come to seven, maybe seven-fifty out the door.

The guy who spent his Sundays purring into a microphone went silent, seemed to be staring into space, maybe lost in calculating how much he had in his checking account, or possibly meditating on the obvious cynical question, “Why would a stranger risk getting fired to make such an offer?”

I broke the silence, asked if he would consider doing me a personal favor in return: Play my favorite new album in its entirety the next day, Sunday, during his weekly New Album Preview show.

Dave acknowledged that he’d been doing that show for a year or so, but the regular DJs had been announcing another album all week as his upcoming feature, no way could he pull a last-minute switch. Awkward silence.

Then he must’ve gotten a vision of those walnut towers pumping “Rocky Mountain Way” into his living room because his next sentence was, “How about if I play it next Sunday?”

He stared down at the asphalt, shifted from foot to foot, appeared to be organizing his thoughts. He straightened up, looked me in the eye and asked three questions:

“Now this album, it is soft rock, right?”

“Yup!”

“It doesn’t have language that could get me in trouble with my boss or the FCC, does it?” I thought about the last track on side two, took a moment to choose my words.

“Major-label artist, man. Who’s cleaner than Columbia Records?”

“And it is a new release, right?” The idea of lying paralyzed me for what seemed like forever, then I had a thought.

“Hasn’t even hit the airwaves yet!”

Dave didn’t ask whether it happened to be a certified, dead-and-buried stiff, and I kept my mouth shut for once.

We split up, walked separately back into the store, milled around aimlessly, like two guys pretending not to know each other, two guys about to steal something. When the coast was clear we squirted behind the counter where I showed him the cost sheets for his new system.

While Dave hauled out his checkbook I dashed back to the record department to grab one of the five Piano Man albums from the reserve stash under the counter.

* * *

WITH NEW LIFE breathed into The Epic Struggle, the next day, three of us – Marty, his taciturn friend Veg, and I – convened at the house to talk strategy. I laid the petition list on the kitchen table. We looked it over and quickly agreed that everyone who’d coughed up a number needed to get a call.

Marty laid out the plan: Remind them they’d signed the petition; ask them to call the station next Sunday, a little after 2 o’clock, when Dave’s New Album Preview show starts; have them write down the time and call-in number; and make sure they tell whoever answers that they love the album.

Veg was eager to help his best friend but wasn’t blessed with the kind of cranium that readily stores the fine points of sequencing and phraseology. After rehearsing for half an hour with only modest progress we agreed a live practice run might help loosen things up.

Marty picked a name on the list, dialed the number, handed Veg the phone. He managed to get through the first part of the call OK, considering. Then a stricken look came over him.

“Uh, Marty, the lady wants to know what to say if the station asks her why she likes the record,” he said, his eyes big. He hadn’t put his hand over the phone, so the lady could probably hear the discussion, which made me nervous. Marty offered some platitude or other, which Veg did his best to repeat into the phone.

The lady balked. Veg looked at Marty and me, could tell it wasn’t going well, and started to panic. I was getting the queasy feeling our moonshot was destined to stall on the launchpad. Finally, I leaned forward and whispered in his ear, “Just tell her to say it’s the greatest album since Sergeant Pepper’s.” That didn’t seem to alter the look on Veg’s mug, so I added “… by, you know, the Beatles.”

Veg shredded the syntax, but somehow the Sergeant Pepper’s part came through and she was satisfied.

Veg was relieved, offered to take the whole petition home with him, said he’d try his best.

Six days later Veg rattled into the parking lot in the spastic Vegmobile, said in a quiet, tentative voice that he’d dialed every number, managed to get around 120 people to promise to call in on Sunday afternoon.

I was having trouble believing such a quiet, sensitive guy could’ve found the grit to ask that many strangers for a favor. But Veg insisted he was telling the truth, offered to call some of them back on Sunday morning to remind them before the album went on the air.

Marty and I looked at each other. Yeah, that sounded like a real good idea.

* * *

AT 2 O’CLOCK ON SUNDAY, MARCH 3, 1974, Dave Butler cued up the first track on side 1, “Travellin’ Prayer,” and played both sides of the album straight through, without interruption. I tried to call and thank him three or four times while it was playing, couldn’t get through. Tried again around 6 p.m., but the line was still busy.

Dave called me at work Monday morning.

“The switchboard was lit up for hours, jammed, man, never seen anything like it!” he boomed, betraying no sign that it could’ve been the result of something other than a spontaneous groundswell.

I was feeling pretty clever again, but, like the previous time, it didn’t last. Dave’s next sentence was, “Tell me, what’s the single, which cut am I running with?”

In that moment I realized that neither Marty Sherwood, owner of that Gold Record, nor I, Hooter McNabb, Music Critic, had a clue what we were doing. I’d been trumpeting an artist. Marty had been promoting an album. Together we’d been leading some cow-town counter-culture cause.

DJ Dave didn’t need any of those things: He needed a song. Marty and I hadn’t gotten that far.

“Gimme a second,” I said, my heart racing as I fast-forwarded through the most tuneful tracks in my head, but there were a couple of radio-worthy cuts on the album, and I was getting freaked out that we were this close and I could pick the wrong one, blow it at the end.

“Marty used to break singles at KYNO, got a Gold Record on his wall, man. I’ll ask when I see him and call you right back,” I said, a little tentatively.

The quiet engineer with the mahogany vocal cords positively bellowed: “I need the answer now!” I froze. My know-it-all McNabb persona was nowhere to be found. Finally, I managed to answer, timidly defaulting to the safest option:

“Think maybe you could just play the title track until Marty tells us what the hit’s gonna be?”

I figured that if that track didn’t take off, it’d be Columbia’s fault for picking the wrong song for the title of the whole album. It was an act of cowardice, and I knew it before I got the sentence out.

After a few moments of dead air, Dave said matter-of-factly, “OK, I’ll run with that for now. Call me right away if Marty says it’s a different song.”

Then, in a quizzical tone that still rings in my ears, he asked, “Do you think the album sounds like Sergeant Pepper’s? I don’t hear that. Funny, almost all the call-ins mentioned it.” I felt my face turn red.

* * *

KFYE PUT ‘PIANO MAN’ INTO HEAVY ROTATION on Monday, March 4. The following day, one of Marty’s old KYNO colleagues rang Sun to confirm that the new song in hit rotation on soft rock 94 was by the same guy Marty had pitched a while back, the one that stiffed. I told him Marty was out, will call him back, but, yeah, same artist, Billy Joel.

Same guy called again less than an hour later, rattled, said he just got off the phone with Columbia, and they had nothing to send, no album, no single, nothing. Columbia is the biggest record company in the world, and they’re KYNO, for God’s sake, and somehow a little station down the street scores a copy, puts it into heavy rotation, and KYNO is shut out? What the hell is going on?

Marty returned, confirmed “Piano Man” as the hit song, then dialed KYNO from the phone near the cash register, held the receiver out a little so I could lean in and hear, then said, “I’m on my way.”

He reached down and pulled the last four copies from the reserve stash. We looked at each other, thinking the same thing: “Oh my God, it’s really gonna happen!”

After his KYNO stop, Marty dropped off a copy at three other, now-forgotten pop stations in town. When he rolled back into the parking lot in Toad, his old clapped-out green Volvo, there were no albums left.

Billy’s future was no longer in our hands, let alone Columbia Records’. It was in the hands of a very particular radio station in the middle of the San Joaquin Valley.

* * *

KYNO USED OUR RESERVE-STASH LP to make a “cart” of the title track, and debuted it that afternoon, Tuesday, March 5, 17 weeks after the single’s initial release on November 2 of ’73. By the time I connected with Reuther at the end of the day he’d already relayed the breakthrough to his boss down in LA, who’d relayed it up the chain to Columbia in New York. No one there needed to be reminded what the consequences of the KYNO/Drake connection could be.

They were already scrambling to pull together the stampers, masters, artwork, everything needed to do another press run down in Santa Maria, where it was all-hands-on-deck. Albums and the single would start shipping within 24 hours.

“Hooter,” he said, “if it catches on in the Bay Area and down in LA, that little stiff of yours could go national!”

* * *

FOUR DAYS LATER OUR “LITTLE STIFF’S” TITLE TRACK was the subject of a blurb in Billboard‘s March 9 issue, with a photo of Billy and a lead that read: “It took some three months of dogged promotion by Columbia to get the writer-singer-pianist’s first single on their label charted. But their faith is repaid as the album jumped 25 chart positions in a week.”

Billboard‘s chronology was off (it had been 4 months and 1 week since the single’s release), and the part about Columbia’s “faith” and “dogged promotion” caused a few paroxysms of eye-rolling at Sun, KYNO, and Reuther’s office up in San Francisco. As he’d said at the beginning: “Just the way it works.”

But the song I suggested that DJ Dave play as a stalling tactic “until Marty tells us what the hit’s gonna be” was just getting started.

A few days later, March 13, KYNO moved “Piano Man” into A-list (Top 30) rotation, something not missed by the hundreds of Drake-programmed stations around the country. The following month it entered the Billboard Top 25 list. It would eventually be enshrined in Rolling Stone’s list of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.”

But the Piano Man phenomenon wasn’t limited to a radio single with that infectious “sing us a song, you’re the piano man” hook. The album with the froggy eyes had unusually strong legs as well. Eighteen months after Dave spun the whole thing on his commercial-free New Album Preview Show, the RIAA certified it Gold. Platinum certification followed, then Double-Platinum, Triple-Platinum and Quadruple-Platinum.

It’s still going, been reissued, special deluxe editions, the works.

An amazing journey for an album that started its rise from the bottom of the Tower of Scorned Flotsam, next to my waterbed.

* * *

PIANO MAN WAS ONLY THE FIRST of a string of Billy Joel hits spanning five decades. He’s gone on to sell over 150 million records for Columbia, become one of the biggest pop artists of all time. He’s still selling out concerts around the world.

* * *

A FEW WEEKS AFTER IT TOOK OFF, I threw a switch I didn’t know I had: started winding down the Piano Man/Sun Stereo/music critic chapter of my life, filled out a late application for UC Santa Barbara, handed in my notice at Sun, and sold off my stereo gear and albums to come up with tuition.

That fall, I crammed my books and clothes into my little Beetle and headed to Santa Barbara. I packed a few keepsakes of my Hooter McNabb days, including my Rampage clippings and that promo copy of Piano Man. The following year I packed them up for the move to UC Berkeley.

I still have them.

– E N D –

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS:

The first person I need to thank is my old roommate, Marty Sherwood. We hadn’t connected in 44 years but when I finally found him – in a Bay Area hospital recovering from a heart transplant – it felt like it’d been a week or two. He’s enjoying life with new vigor and a muscular new ride in his garage. Ride on, Marty!

I owe a special thanks to Ken Reuther of Columbia Records. Ken had a 40-year music business career for major labels in New Orleans and San Francisco, where he still lives and is a former president of the San Francisco Tour Guides Guild. He’s also the Guild’s unofficial city historian – something that didn’t surprise me, given his sharp memory of the details of our interactions 45 years earlier. Ken started his career in New Orleans as Southeast and Southwest Regional Promotions Manager at Paramount Records, a small company that put out Billy’s first release, Cold Spring Harbor.

Thanks also to Ken’s Columbia colleague in New York, George Chaltas, who worked to promote Piano Man’s release in the Northeast. Ken and George gave me general record-company context, corroborated details of what was on/off Columbia’s weekly priority lists in late ’73/early ’74, and clarified how long a new release could go without charting before it was written off as a “stiff” in those days.

When I reconnected with my manager at Sun Records, Michael Chakerian, his first recollection was of relaying the bad news that there were no more Piano Man albums available or planned, then going back into his office and re-emerging 20 minutes later, only to be confronted by my electric-yellow protest posters on the walls and a noisy petition campaign in full swing. Mike, your vivid description of the scene made my fury and frenzy feel fresh again.

Special thanks to the old Sun Stereo team who shared memories and details with me after decades of radio silence: owners David Dwelle and Tom Wirht; audio manager Larry Henderson, salesmen Steve Reimann and Glenn Kumagai, and engineer Tim Johnson, all of whom I managed to connect with for this story.

Steve, if you’d bought reliable transportation instead of that troubled Norton Commando, I wouldn’t have had to pinch-hit for you that Saturday, and the rest of this story simply wouldn’t have happened. In a roundabout way, your questionable transportation decision had the effect of giving Billy one last chance at stardom. It was all he needed.

I’m indebted to several long-time Fresno radio people who took my calls, shared their recollections, and read drafts of this story along the way. Greg T. Elliot, along with Dave Butler, was one of KFYE station owner Dick Ingram’s first hires when he launched the station in ’72. Sean Conrad was program director at KYNO during Marty’s days there; his recent memoir, Kickin’ Out the Jams, captures the zany spirit of the times.

Thanks also to KYNO veterans John Ostlund and Kyle Mack, who dug through the station’s copious archives and sent me photos and weekly playlists of the time. Central Valley rock legend and radio historian Ray Appleton put me in touch with other radio personalities who filled in various background details. And KFYE’s Karen Franz dug into the history of station personnel for me. Thank you, all four, for taking my many calls, many of which ended with my “That should do it … oh, just one last question …” routine.

I never achieved my dream of writing for Ben Fong-Torres when he was famously editing Rolling Stone, but he graciously connected me with Top 40 radio archivists who offered useful background. Thanks, Ben.

Heartfelt thanks to editor Lisa Chakerian, who took time to critique and improve my earlier drafts.

Special thanks to my high school buddy, Mark Harry, whose memories of “The Billy Joel Caper” brought some of the color and vibe of those days back into sharp focus.

Lastly, extra special Thanks to my spirited wife, Hanne, who’s been hearing little pieces of this story since she agreed to stand outside a concert venue in Munich with me one freezing night in late ’77 or early ’78, hoping to catch a glimpse of Billy when he emerged after his concert. We didn’t see him, but it was while standing there in the snow with our arms around each other that I decided that someday, when Billy’s about ready to hang it up, I just had to write down my Piano Man story.

FURTHER EXPLORATIONS:

Fred Schruers, Billy Joel: The Definitive Biography (Three Rivers Press, 2014).

Marc Fisher, Something in the Air: Radio, Rock and the Revolution That Shaped a Generation (Random House, 2007).

Ben Fong-Torres, And the Hits Just Keep on Coming: The History of Top 40 Radio (Backbeat Books, 1998).

Sean Conrad, Kickin’ Out the Jams: The Purple Haze of my Crazy Daze in Radio (Black Opal Books, 2013).

Derek Thompson, Hit Makers: How Things Become Popular (Penguin Books, 2017).

The New York Times, December 1, 2008: www.nytimes.com/2008/12/02/business/media/02drake.html.

Billy Joel website: www.billyjoel.com

IN MEMORIAM:

Some of the people who played important roles in the story are no longer with us.

I’d left Fresno for UC Santa Barbara shortly after I offered DJ Dave Butler that killer deal on the ESS AMT-1b speakers, Sony STR-7065, and Dual 1218 turntable in Sun’s parking lot that fateful Saturday. I can only assume that, when he took delivery, one of the first cuts he played was “Rocky Mountain Way.” When I started filling in the chronology for this story back in November 2017, Dave was one of the first people I tried to get in touch with. I was saddened to learn that he’d passed away a few years earlier, at the age of 66. (https://www.dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/fresno-ca/david-butler-6139542).

Veg’s real name was Samuel Jeffrey Boghosian. He acquired the “Veg” moniker due to his strikingly dilapidated VW Beetle – the Vegmobile – sporting the color and complexion of a diseased avocado skin. Although he never officially worked at Sun Stereo, Veg and his iconic transport were the closest thing the store had to a mascot. We all loved him. He passed away February 3, 2003 (http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/name/samuel-boghosian-obituary?pid=819383&view=guestbook).

Lastly, I had only a single, hour-long conversation with Piano Man’s producer, Michael Stewart, who called after he’d read my shorter account of this story in the August 1987 issue of Sacramento NPR affiliate KXPR’s program guide. He confirmed he and Billy had been told it was “time to go back to our day jobs,” but once the album took off, seemingly out of nowhere, Columbia insisted on using their in-house producers instead of him for Billy’s subsequent albums. Despite that disappointment, Mike said Piano Man was the high point of his career. He was previously the leader and chief songwriter of The We Five folk-rock group, whose 1965 single “You Were on My Mind” reached #3 on the Billboard singles charts. It remains a staple of oldies stations. He passed away November 13, 2002 at age 57 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Stewart_(musician)).

© 2018-22, Keith Yates. All Rights Reserved.

Michael did produce “Streetlife Serenade”, before he and Billy went their separate ways. Billy produced “Turnstiles” himself after firing Jimmy Guercio and this enabled him to record it with his own Long Island backing musicians.

Of course, as we all know, Phil Ramone produced the next six albums starting with “The Stranger”.